Research

Design Collections | Design Knowledge

March 22, 2025

Design Collections

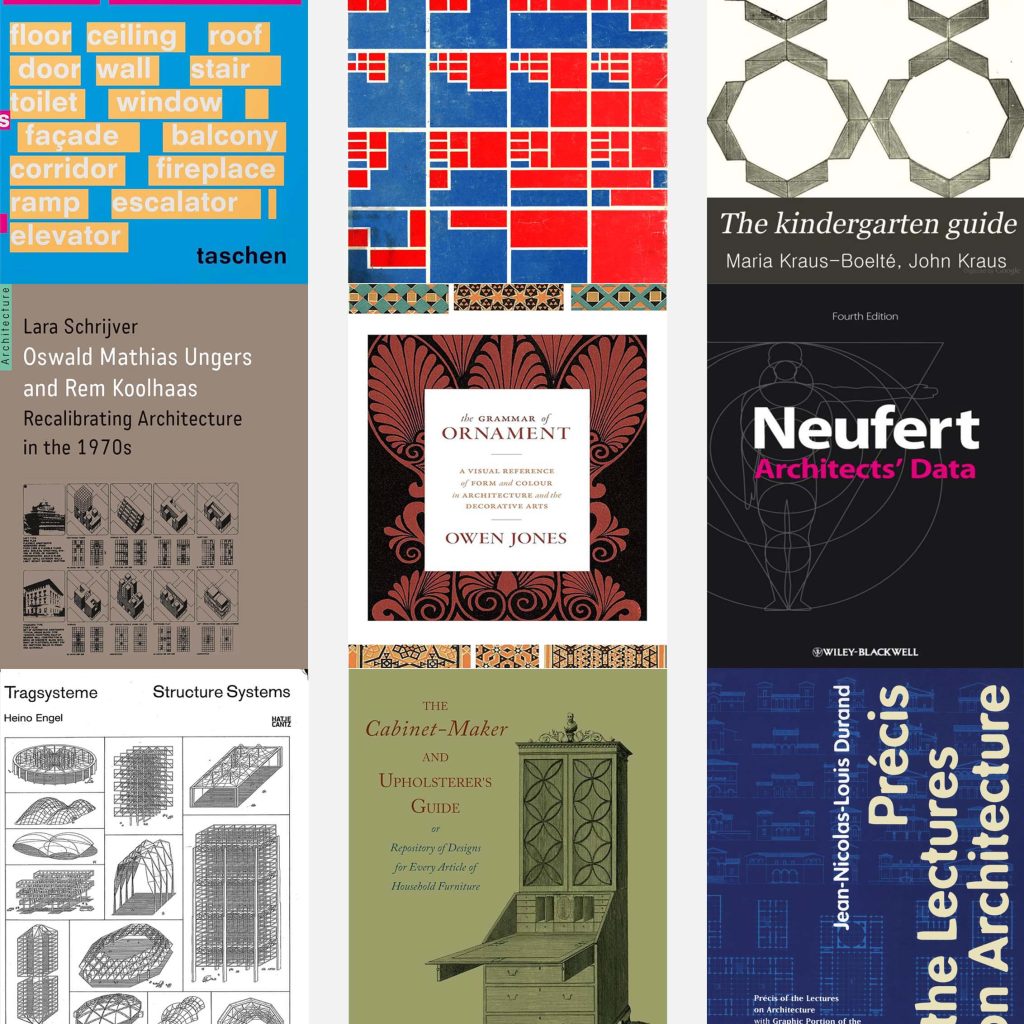

The proliferation of design collections overlaps with a broader adoption of technologies for printing and graphic design in the 18th and 19th centuries. This contributed to the public dissemination of art, design, and architecture catalogues, generously illustrated with drawings and classifications of design artifacts of various scales. For example, The Grammar of Ornament (1856) by Owen Jones is a design collection that exclusively documents illustrations of ornament designs from nineteen human cultures. Other collections contain illustrations of plans and elevations of buildings, structural systems, and building components (e.g., doors, windows, and columns). Some examples are Langley’s The City and Country Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs (1740), Durand’s Précis of the Lectures on Architecture (1802–5), Neufert’s Architect’s data (1936), and Engel’s Structure Systems (1967), among many others.

Design Knowledge and “Data”

Design collections represent specific knowledge areas of architecture and design and contain a set of generated and recorded design instances – typically using two or three-dimensional graphical representations – that exemplify that knowledge area. In this sense, design collections can be understood as “data” that represent design knowledge. However, a design collection is not by itself a “dataset” in terms of the meaning that the term receives in today’s machine learning (ML) and data science research. Indeed, the examination of design collections from architecture and design leads to a broader question: What makes a design collection different from traditional datasets used in ML or data science?

Design collections exemplify the following characteristics:

- A small sample size compared to the large-scale deep learning benchmarks that contain thousands or millions of images of common objects in-context and natural scenes. Design collections are created manually by human experts (architects, art critics, engineers, collectors), an experience acquired over many years of training and observation of human-design artifacts.

- Imbalanced class distribution resulting from the data-scarce nature of architecture and most design fields. For example, ML algorithms are prone to focusing on the larger classes within a dataset and are much worse at generalizing over new samples that belong to underrepresented classes.

- Intricate visual details and pattern variety across a collection which, in combination with a small sample size, poses significant algorithmic and learning challenges. Relevant research areas in ML outside of architecture and design are fine-grained visual classification and domain adaptation for medical imaging and for images of plant specimens.

- Incompatible formats for direct application of learning algorithms. Design collections must be digitally curated to become usable in algorithms for learning, a task often involving a combination of manual and automated methods relying on expert knowledge. In contrast, most ML benchmarks are created from existing digital images (or other data types) that are automatically crawled from the internet or are extracted from public/private digital databases.

These characteristics make design collections an important and largely underrepresented source of potentially useful and impactful datasets for ML research and for delving into the broader question of human intelligence.

The specificity design collections provide (i.e., that they document particular design objects) provides new benchmarks for diverse fields, such as fine-grained visual recognition, data-efficient learning, interpretability, art-historical research, architectural style analysis, and cultural heritage. For example, designers, architects, or humanities scholars may use these collections to discover previously unknown visual links between design objects belonging to different cultures or generate informative narratives about their origins, visual features, cultural meaning, etc.

Design collections also raise traditional questions at the intersection of aesthetics and ethics, such as originality, authorship, copyright, and cultural or disciplinary bias. These issues underscore the need to probe deeper into the aesthetic intelligence of discerning one design (or aesthetic object) from another – a learned human competence that remains central in architecture and related design areas.

Related Work

This portfolio item is based on the following publications:

(1) The ACM Conference article “JONES-19: A Cultural Image Dataset Based on The Grammar of Ornament,” describes the curation of a small-size design collection that focuses exclusively on ornament designs.

(2) The journal article, “SHREC’21: Quantifying Shape Complexity” (Computers & Graphics, Vol. 102), describes the curation of a small-size design collection of 3D shapes that was generated synthetically using parametric design software.

(3) The NEXUS’25 Conference article “Description Changes in Architecture: Identity Rules in Shape Grammars and Multiplicity in Design Datasets,” asks whether architectural or design innovation can be encoded in design data for AI. It proposes rule-based methods for capturing architectural change and innovation computationally.